Today, by request, I’m going to take a crack at pinning down a definition for that mysterious term “speculative fiction.” [For more definitions and genre musings, check out the rest of my “What Is Genre Series” here!] If you’re a writer, reader, or movie-goer you’ve probably come across this phrase before. You might have also heard it shortened as “spec fic” (spec-fic).

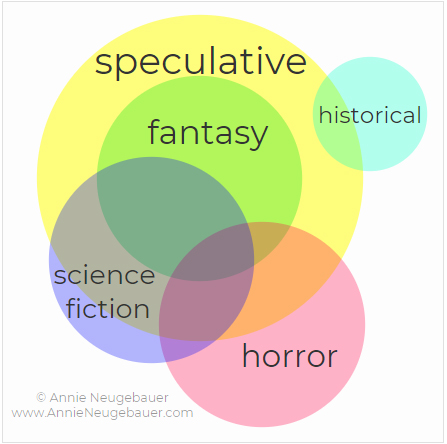

So what is speculative fiction? The fast answer: fantasy, science fiction, and horror. But as you can see by my hastily-drawn diagram [UPDATE: I finally made a nice diagram! Yay!], that oversimplification causes some serious problems. For one thing, both horror and science fiction can include works that aren’t actually “speculative.” (We’ll get to that in a minute.) For another, while those three are the dominant genres involved, they aren’t the only genres involved, and no one likes to be excluded.

That moves us to the need for a more accurate definition. The key here lies in the root word: speculate. Think of this in terms of “what if” and you’ll see it. So now you might ask, “But doesn’t that make all fiction speculative? Fiction, by definition, is untrue, so all of it involves some degree of speculation.” The difference is in what’s being speculated upon. Speculative fiction is fiction in which the author speculates upon the results of changing what’s real or possible, not how a character would react to a certain event, etc.

Therefore, the thing being speculated upon must be more elemental than character or plot. Speculative fiction is any fiction in which the “laws” of that world (explicit or implied) are different than ours. This is why the term “world-building” usually goes hand-in-hand with “speculative fiction.” If you’re changing our world or creating a new one, you’re going to have to do some work so the reader/viewer understands the new “rules.” Don’t let the word “world” throw you off, though. The defining line between fiction and speculative fiction is not so much scale as it is ‘what’s possible’ in reality. (Scale is more of a byproduct, and an optional one at that. Speculative fiction can be and often is small in scope–think a single character’s life vs. global battles.)

So dropping a bad guy into a nest full of alligators, while thrilling, isn’t “speculative” because it could really happen in our world. Dropping a bad guy into a nest full of mutant alligator-sharks is “speculative” because it isn’t possible in our world; the author must “speculate” on how that would go. (And I’m guessing the answer is “not well.”)

Another example: a movie in which two astronauts get lost in space isn’t speculative because it could really happen within the realm of our existing knowledge of the world, as terrifying as that may be. A movie in which a group of astronauts discover an alien life form is speculative because–according to our current knowledge–it couldn’t happen in real life, since we know of no other intelligent life forms. See the difference?

Speculative fiction takes our existing world and changes it by asking “What if…?” (What if monkeys could fly? What if zombies were real? What if the Nazis had won World War II? What if one man had x-ray vision?) This opens up the first definition — fantasy, science fiction, and horror — to include other genres as well, such as alternate history, weird tales, dystopian, apocalyptic, time travel, superhero, etc. It also excludes science fiction and horror that doesn’t speculate (i.e., horror without supernatural elements, or science fiction based on current technology).

Now that we have a good definition to go on, let’s take a more detailed look at my little diagram.

In area 1, we have the overwhelming component of speculative fiction: fantasy. By definition, all fantasy is speculative. This includes all subgenres, such as epic, soft, urban, and magical realism.

In area 2, we have another large component: science fiction. As I mentioned above, sci-fi is usually but not always speculative. (When it’s not it becomes section 3.) Speculative sci-fi often includes the sub genres of space travel and time travel.

In area 4, we have the third part of the main triumvirate: horror. Horror is frequently but not always speculative. Horror based on true events or without any supernatural elements falls outside the speculative ring (section 5). Speculative horror includes paranormal, creature, and weird tale to name a few.

Sections 6 through 10 are probably pretty self-explanatory. If you combine speculative sci-fi with speculative fantasy, for example, you might get superhero fiction. In all those little overlapping sections, it’s really a game of mix and match.

Section 12 is historical fiction without speculative elements, such as a fictionalized rendering of a real battle or a fictional character living in historically accurate settings. Section 11 is historical fiction with speculation thrown in, such as supernatural elements added, a shift in the real timeline (alternate history), etc.

Finally, there’s lucky section number 13, which holds all of those speculative stories that don’t fit neatly into fantasy, sci-fi, horror, or historical. These might include dystopian, weird tales, or surrealism.

As if that weren’t all complicated enough, if you shift some circles around you can build and blend your own genres. Expand “historical,” for example, so that it overlaps with “fantasy” and you’ve got historical fantasy (think vampires in the Victorian period or elves fighting in World War I). Throw in a healthy dose of fear and you might have historical horror.

The possibilities are really limitless, which is perhaps why so many people get confused by the term “speculative fiction.” If you find yourself getting lost, go back to the basics: could this world really exist according to our current knowledge of reality? If the answer is yes, it probably isn’t speculative. If the answer is no, it probably is speculative.

At this point you might be wondering, Does this mean that “speculative” changes over time? My answer is yes. As our knowledge and technology change, so does our interpretation of what’s “possible.” Technology in futuristic books written twenty years ago might not be speculative at all anymore. No to mention that individual beliefs can affect the definition, too. That’s how you get books about ghosts and aliens on the “nonfiction” shelf; some people believe these are already a part of our reality. Technology changes, knowledge grows, beliefs shift–and these are all things that inform our concept of “what’s possible.”

As you can see, the lines on all the circles I’ve drawn could be a little blurrier, but I hope I’ve shed some light on the general concept. As always I’m happy to answer questions below, or to hear your take on things!

Fun post, and very informative. I will confess to being all-in right now on my creative nonfiction, including memoir, personal essays, and my personal passion, biography. But someday I’d like to write some #12, which puts me outside of your speculative bubble but as you note is also speculative in its own way.

Thank you, Patrick! Yes, almost all history is speculative in some way — more so the further back in time you go, since we can know less and less about what really happened/how things really were. Sounds fun!

That’s a great way to break it all down. I’ve just started querying my YA novel and I’ve been torn between labeling it Speculative Fic and Sci-Fi. (I’m trying to avoid the dreaded D word (dystopian!). I think Sci-Fi sounds more specific and is accurate for my work, but since it does include elements of dystopian, some horror, as well as romance, it feels like the broader Speculative may be the way to go in order not to bog down the query with too many genres at once. My only fear is that Spec Fic may be too broad for some agents. Do you have any thoughts about using Speculative in queries?

Thanks! That’s a tricky problem, and I’m no expert, so take my thoughts with a grain of salt. Personally, I would tailor to each agent. If you’re querying someone who loves sci-fi, I’d go with that. If they don’t represent a lot of sci-fi but are open to spec-fic, I might choose that label for them. The only thing I definitely wouldn’t do is try to describe every aspect of it genre-wise. Agents seem to be universally put off by too many labels. I would choose either the one that most captures the “feel” of your manuscript or the one that will be most appealing to the agent in question, and then maybe hint at the other things by carefully chosen comp titles. (I.e.: one dystopian, one horror, one romance, etc.) I have more on how to choose comp titles in this post, if you’re interested: https://annieneugebauer.com/2012/08/14/finding-comparables-for-your-novel/) Good luck, Michelle!

I think that’s good advice. Thank you! Off to read the Comp Titles post now.

Best explanation I’ve ever seen of this. Thanks, Annie!

Wow, thanks Regina!

Another fabulous genre explanation, Annie! Your Venn diagram approach helps a lot. I’m wondering if you had any examples for section 3, where sci-fi is not speculative. Thanks for bringing clarity and an opportunity for discussion to the jungle of the multiple genres. I can imagine the support group now: stories sitting in a circle. One stands up and says: I’m Mo and I’m speculative. My dad’s sci-fi and my mom’s horror. They want me to be like them, but but but… I can’t. I’m speculative. 🙂 It’s ok, Mo.

Hahaha! You’re a hoot. 🙂 I think horror would be the stepchild, actually. Brooding in the corner, annoyed that it doesn’t get the same attention and respect as it’s big siblings sci-fi and fantasy…

I wish I had an example for section 3, but I honestly don’t read a lot of sci-fi, so nothing comes to mind. Imagine if Demon in the Freezer were fictionalized, or if The Da Vinci Code were heavily science-based. I’m sure there are plenty of “science fiction thrillers” that fall into this category.

Ha! Yes, the brooding stepchild. 🙂 Brilliant. Thanks for the tips re section 3.

Awesome post, as usual! I love speculative fiction but was always curious about a definition. Now I know 🙂

Thanks so much!

What a fantastic, explanatory, and organized approach! I really appreciate your “What is Genre” posts. It’s how I found you (“What is Literary Fiction)! 🙂 I like how you always open up seemingly simple posts (i.e. an explanatory post on a genre) to much bigger concepts, like “Does ‘speculative’ change over time?”

Thanks, Ashley! I’m glad you liked it; I bumped it up just for you! 🙂

I should have known there would be charts/diagrams. 🙂

Very thorough and informative post, Annie. You get all the cookies.

Haha! I’m a diagraming fool. Thanks Brian. (I love cookies!)

I love this – you analyzed and explained it all so well. That graph is excellent. I want to reside in the sweet spot, #9, the combination of scifi/horror/fantasy. That’ll be my next novel … if I can just get the current one finished. 😉

Thank you, Lexa! I love that middle spot, but so rarely see it done. Sounds like a blast!

Helpful, Annie. Thanks! So what would you call #9, then, especially if it has a large dose of romance? (I’m not querying this piece but have decided to SP, so I need to figure this out for meta-data.)

Thanks Jan! I’m glad it was. For marketing/explanatory purposes I would go with either “speculative romance” or just “speculative” (depending on how much you want to emphasize the romance). That’s the beautiful thing about the term “speculative fiction”; it encompasses so much and provides a label for things that blur or combine sections like yours.

But for behind the scenes stuff like meta-data I would probably include all 4, if you can! If you tag it with “fantasy,” “science fiction,” “horror,” and “romance” you’ll be hitting the right target audience, right? I’m no expert, but that’s what I’d probably do! I wish you the best of luck with it.

Funny you wrote this right now, Annie. I was wondering about spec fic last week, as I was researching markets for one of my horror shorts. I Googled what it was, but never got as good an answer as you give here. Love the graphic with the circles – that’s perfect!

That makes me so happy! I love it when my little musings help people. 🙂 Thanks so much, and good luck with the horror short!

And . . . now I feel totally justified for having been so confused before. Nice job here, Annie! WOW! I can’t even imagine how long it takes to write these genre posts. You totally nail each one.

Thank you, Nina! Yes, I totally understand why there’s so much confusion. I mean, I needed a freaking diagram to clear things up! I’m glad it helped though; that makes the effort totally worth it to me. 🙂

This is so helpful… my last WIP (that I’m shopping around) is historical time travel which I see as Section 11! So, cool! I’ve stopped short of calling it “speculative,” because in my mind that had a certain connotation, but your explanation makes it clear that it is at least speculative in nature. Really great post, and it makes me want to write a lot more speculative fiction! Thank you.

Awesome! I’m so glad. Historical time travel sounds very cool, and definitely speculative. I hope you do really well with it, Julia!

Wow! I’ve wondered about speculative fiction and how it fits into the genre landscape. This post is very helpful.

Thanks Missy!

You’re so good at this, Annie! You should totally teach an online course about genres. You explain it all so clearly and in an engaging way.

Aw, thank you Natalia! I love teaching, so that’s definitely something I’d be up for!

Nice, and it has a map even. Very cool. Though, is speculative fiction, literary? (I’m kidding! I’m kidding! PUT THE BUTTONS DOWN!)

Thanks! And… it can be! *raises the buttons over her head* *isn’t quite sure what to do with them*

Good analysis, much deeper than I would go. Thanks!

Thank you! It was my pleasure.

Pingback: No Wasted Ink Writer’s Links | No Wasted Ink

This was an interesting take, but I do gave some quibbles; first, I am familiar with “sci fi” (which I prefer to call SF or science fiction) and I can’t think of any works I would identify as science fiction that doesn’t speculate. Modern day thrillers based on scientific concepts are thrillers, not SF, as speculation/extrapolation of science and technology are a foundation if the definition if the genre. No spec, no SF.

Alt. history, time travel, etc are sub-genres of SF and I think their inclusion as separate elements confuses the picture.

A long time ago I was taught a taxonomy for writing. it broke things down first into fiction and non-fiction. on the fiction side it then started with a major branch labeled ‘fantasy’. Below fantasy was speculative fiction, myth, etc. You seem to be inverting this long established taxonomy.

Hi Steve! You have some interesting perspectives. I agree with some and disagree with others, but I very much so appreciate your comment! I hope you take my reply in the spirit of discussion rather than argument.

I think you’re probably right about non-speculative science fiction being a science-heavy thriller, which would just be labeled a thriller, and most wouldn’t consider it SF anymore. (I’m very surprised by your preference of one form of science fiction/sci-fi/SF over another. I’ve never made much distinction myself, but my apologies if one offends for some reason.) I don’t think that changes the fact that it’s technically science fiction, though — just not what we recognize it being called by. I tend to think of genres through a lens of “what’s most logical” rather than “what’s most common,” and I completely understand that that makes some people uncomfortable.

I have to disagree that history and time travel are sub-genres of SF. I think they can be, absolutely — which is why I mentioned the shifting around of the circles to create different overlaps — but they often have no science basis at all. In many time travel stories there isn’t even an attempt to explain the device; the time travel itself becomes more akin to magic than to science. Not to mention that not all historical fiction uses time travel; much of it just takes place in another time, with or without modification. And then also, if we go far enough back in time where there’s a lack of written history, any fiction necessarily becomes speculative no matter how based on fact in may be.

It sounds to me like the taxonomy you’re familiar with is breaking down genres according to popularity, establishment, and/or prestige rather than my method, which involves ignoring those things and looking at the basics of each genre. For example, in my eyes fantasy simply can’t be the parent category, because fantasy must be speculative but speculative doesn’t have to be fantasy. Therefore speculative is the parent genre. But of course that’s just my way of looking at it, and you’re free to use whatever breakdown you like best. I really appreciate your thoughts!

Annie, thanks for the reply.

In general, it seems to me that your analysis is not taking into acount the history of development of these genres – and you seem to be basing some of the analysis on tropes rather than the overall theme(s) of a particular story.

“Time travel” stories in which the time travel element is fantastical, unexplained, ungrounded, etc are stories that may use time travel as a setting device, but they are not “time travel” stories. They’re stories that use some hand-wavium time travel methodology to change the scene. If, on the other hand, the story is about the consequences of time travel, creating time travel, using time travel in a controlled and pseudo-scientific manner, then they are properly “time travel” stories and belong under the heading of science fiction.

The primary feature defining the difference is how the science is handled and whether or not the context of the story is, essentially, the impact of something scientific on humans/human society. Same holds true for alt history, etc.

Even a few decades ago there would be no need to discuss this; its only become an “issue” since mainstream literary writers have begun to appropriate themes and concept from genre – usually with no deeper engagement than ‘its a nifty device I can use for my otherwise mundane tale of whatever’.

On the scifi/SF thing: historically, “sci fi” was rejected by the science fiction community and came to be received as a term of derision. Within the SF community we began pronouncing it “skiffy” and used the term to indicate that someone was clueless about the genre, or only had a fleeting, surface-level engagement with it. In more recent years it has become the more popular term for the genre – primarily when referring to media presentations – but some of us still wince when we hear it and prefer the more formal science fiction or SF. the nameless television station taking the name SciFi originally (now syfy) was seen as a perfect name for a channel that produced whale-droppings levels of utter crap that perfectly matched what we would expect from a channel naming itself that.

On the taxonomy – writing is formally divided into non-fiction and fiction. Fiction is further divided into prose and poetry. The next level below prose is fantasy, which itself contains science fiction, romance, “fantasy”, westerns, mystery, etc.

Yes, it seems we have a fundamental difference in opinion as to what constitutes genre. I completely disagree with your taxonomy. Poetry, for instance, is often, if not usually, nonfiction, so stuffing it under fiction is unacceptable to me. I would have the parent categories be “prose” and “verse,” and then I would break “prose” down into “fiction” and “nonfiction.” I also believe the parent genres are somewhat fluid, and despite kicking and screaming on the part of traditionalists, these things change over time with popularity and the birth of new genres. “Westerns,” for example, are pretty rare these days, though they used to be one of the top contenders as far as popularity. Now I doubt it would make the top 10. For another example, “gothic” used to be its own genre, but is now sub-genred under “horror” because horror is more widespread, even though horror came from gothic.

While I think the formation and history of genres is very important, for me it holds little to no place in the labeling of genres. I wouldn’t care, as far as labeling goes, for example, if high fantasy came before any other type of fantasy; I would still put high fantasy as a subgenre of fantasy rather than the parent genre, because there are other “types” of fantasy, which clearly makes it the parent category in my eyes.

So while I respect that your preferred method of naming the genres is based on tradition and history, that simply doesn’t work for me on a logical level. As a writer and a reader, I don’t want my books labeled according to whoever wrote before me; I want them labeled logically so I (and hopefully my readers) can easily find what they’re looking for. The discussion of formation and legacy is an entirely different discussion for me.

The time travel is a perfect example of why I prefer logic to history. You seem to look down on writers who use it as a device, but I would find it hard to credit a statement that The Time Traveler’s Wife, for example, “doesn’t count” as time travel. It most certainly does, despite the device not really being explained (from what I’ve heard; I haven’t read it). If you were to take away the time travel you would have no book left; to me that makes it decidedly time travel. Now, readers are free to dislike that, but I simply can’t get on board with saying it doesn’t belong in the category of time travel just because it doesn’t handle the device the same way as the first people who handled the device. There’s science-based time travel, and then there are others, and to me they all seem quite obviously “time travel,” because they’re all traveling through time.

I didn’t know that about the term sci-fi’s stigma; thank you for telling me about it. My intention is certainly not to disparage.

Fiction v. Nonfiction

Texts are commonly classified as fiction or nonfiction. The distinction addresses whether a text discusses the world of the imagination (fiction) or the real world (nonfiction).

Fiction: poems, stories, plays, novels

Nonfiction: newspaper stories, editorials, personal accounts, journal articles, textbooks, legal documents

Fiction is commonly divided into three areas according to the general appearance of the text:

stories and novels: prose–that is, the usual paragraph structure–forming chapters

poetry: lines of varying length, forming stanzas

plays: spoken lines and stage directions, arranged in scenes and acts

Other than for documentaries, movies are fiction because they present a “made up” story. Movie reviews, on the other hand, are nonfiction, because they discuss something real—namely movies.

Note that newspaper articles are nonfiction—even when fabricated. The test is not whether the assertions are true. Nonfiction can make false assertions, and often does. The question is whether the assertions claim to describe reality, no matter how speculative the discussion may be. Claims of alien abduction are classified as nonfiction, while “what if” scenarios of history are, by their very nature, fiction.

The distinction between fiction and nonfiction has been blurred in recent years. Novelists (writers of fiction) have based stories on real life events and characters (nonfiction), and historians (writers of nonfiction) have incorporated imagined dialogue (fiction) to suggest the thoughts of historical figures.

http://www.criticalreading.com/fictionvnonfiction.htm

Yeah, that still doesn’t work for me. Poetry can qualify as either fiction or nonfiction just as easily as prose can (including blurred lines). Poetry isn’t really a genre; it’s a medium. It can be about anything, just like prose. Saying that all poetry belongs in fiction is just as untrue to me as saying that all prose does. I think we’ll just have to agree to disagree on this one! But I’ve had fun with the back and forth, and I really appreciate your comments, Steve!

Thank you for this article – I have been struggling to provide some of my reading friends with a good definition of what does and doesn’t constitute speculative fiction. I think each of us who enjoys reading speculative fiction makes these sorts of distinctions for ourselves (and each personal definition likely differs by degrees), but it’s surprisingly difficult to articulate to someone else, especially someone who doesn’t read a lot of spec-fic. I have one friend in particular who loves almost everything I recommend, but has trouble striking out on her own to look for authors and books outside my list of recommendations. I’m going to recommend she read your article; I think it will help her immensely. Excellent piece!

I’m so happy to hear that! Thank you so much for the kind comment. And best of luck to your friend for many wonderful new discoveries. 🙂

I got asked that question during an author panel recently, and I explained it similarly to the way you have here! Even down to specifically mentioning that alternate history would be speculative fiction. Neat. 🙂

That’s awesome! 🙂 Thank you, Julie!

I myself am a hardcore sci-fi/romance with a dash of speculative thrown in reader and writer. (Take a close look at my little picture for proof.) I’ve recently been wondering whether or not my own (unfinished) book is speculative, or just plain sci-fi. (It’s about a present-day girl who wakes up in the future, finds out she’s half-alien, falls in love with a human boy, and must stop a war between Earth and aliens.) A little…cliche, maybe, but I think I’m pretty good at mixing it up.

I’ve now figured out that it’s firmly in the speculative fiction genre. Thanks for this !! 🙂

Yay! I’m so glad this helped clear it up. Yes, your project sounds both awesome and definitely speculative. 🙂

Pingback: Getting our arms around speculative fiction | Imagined Worlds | L.A. Barnitz

Pingback: A non-definitive history of: Speculative Fiction | patricia.leslie

Finally, someone has explained this to me. The diagrams really help. Thanks!

Awesome. Happy it helped!

Great thank you have shared this on our Uni Creative Writing Page

I’m glad it’s helpful!

Excellent post! I write spec fiction and fall in the lucky section #13, more precisely in surrealism. I have looked everywhere to see if I really fell into this category, considering the obvious meaning of the word “speculative.” I appreciate you breaking all this down into very well defined terms.

Thank you! I’m happy it helped you pin it down. 🙂

Pingback: A Word On Specular Fiction | Michelle Writes

I agree with what has already been posted. IT WAS A GREAT DIAGRAM!

i am writing kid books that are speculative. (shapeshifter) That a publisher I met at SiWC has asked me to rework into a chapter book. really looking forward to learning more in this module.

Thanks so much! Good luck with your book!

Annie, once again, you have been so helpful and enlightening! I thank you for your contributions online. I continue to explore the field of writing and this speculative fiction idea is very exciting!

How sweet; thank you! Best of luck to you!

Pingback: What Is Speculative Fiction? | M. G. Herron, Science Fiction and Fantasy Author

Pingback: Genre Angst — Science Fiction vs. Fantasy | BlogBakerDavid

Hi Anne, someone who knows about my interest in speculative fiction directed me to this post. As a writer of what I like to call speculative fiction, I must say I’ve never quite put this much thought into the matter. Your post certainly gives me a lot to think about. I know this post is 2 years old but I think it’s still relevant. I’m going to share it (linking to it) on my blog because it’s certainly worth thinking about.

Hi Tonya! That’s great to hear; I’m so glad you liked it. Yes, please do feel free to share. Thanks!

Pingback: Defining Speculative Fiction - TONYA R MOORE

Pingback: What is Speculative Fiction

Pingback: What is Speculative Fiction? Some Thoughts on Genre – Falling Letters

Pingback: Defining Speculative Fiction – Tonya R. Moore

Interesting, the only point that stuck out is when you wrote “Since we know of no other life forms.” You assume that we are alone in the universe because it’s a popular belief or because you have no experience of your own to the contrary. The evidence, however, states otherwise with millions of people having seen and experienced life other than human. I guess their experiences are all discounted because of some commonly held belief. Oh, that’s right, a long time ago the world used to be flat and no one wanted to fall off the edge. Until, of course, someone proved that it was in fact round. Just a thought and thanks for clearing up the definition of speculative fiction. I have trouble knowing if my writing is more literary or speculative…

Hi Christopher! Yes, you’re right; I do function under the belief that we don’t yet have adequate or undeniable proof of other life. That’s not intended to be an insult or an argument starter. In my post I tried to allow for the shift between people’s disagreeing beliefs about what’s real now as well as the shift over time, as new evidence comes to light. So yes, something written about the shape of the Earth would’ve been considered speculative in one time but not another, as, should we discover hard proof of extraterrestrial life, aliens may become.

As to literary or speculative, it could certainly be both. Literary fiction is sometimes a style, and any genre can be written in that style. I have another post about that here, if you’re interested: https://annieneugebauer.com/2012/05/07/what-is-literary-fiction/

Annie,

I read the other article and it is certainly more detailed. The reason for my interest is that I am currently looking for a publisher for my second novel. I found out the hard way with my first book that finding the correct genre is paramount. My current work is defiantly character driven more than the plot which is always in the background of the story. I have been touting it as dystopian fiction but the literary tag seems to do a better job of describing the writing. As you well know trying to get an agent or publisher and misrepresenting yourself is a no-no.

Thank you for your response and I apologize for the alien comment, I just see it so much that it gets to me. Too many assumptions flying around society.

Chris

(another crazy author)

I understand; no worries! You’re spot on about the importance of pitching your book under the right genre(s). It’s something of an expectations game, in many ways. Have you considered pitching it as a literary dystopian? Good luck, Chris!

Annie,

I would think that the editors have a better grasp on the whole genre thing. The story is sound, definitely dystopian. The entire human race is an experiment in evolution that has been reset several times, the bible flood, Atlantis, the dinosaurs were a casualty of one of the resets. It’s time for another rest and to harvest those who have evolved. That’s what’s in the background. The characters drive the whole story in this book. As usual, I’ll prepare for the worst and hope for the best, thanks for your input.

Chris

That sounds very cool. Good luck with it!

can u please provide me with some what if questions that has something to do with the world today? ex: What if Donald Trump takes his power too far/ abuses it?

Hi Sri. I’m not entirely sure I understand what you’re asking. I think most disaster movies fall into what you’re describing. What if there’s a volcano under LA? What if a meteor hits Earth? Etc. Otherwise you could get into political topics, as you said, or social ones, or even pop culture.

Pingback: Remedial Novel Writing – Lesson 4 | Baby on a Raft

Pingback: EDCI 356: Reading Advertisements as Text in the Creative Writing Classroom: Texts Revealing Societal Norms and Values – Tess Lund

Very informative. Thanks…

I’m glad! You’re welcome.

I connected to this definition for my Indiegogo campaign to create a new speculative anthology (graphic novel) about warfare. Support new enhanced graphic anthology about war. https://igg.me/at/warcomic https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/dddb759e67eade9656d904730d6ca9aa2b67750d939970fdceb839fc7f2cce39.jpg

Dear Annie, thanks for the very informative and usefull post. You see I am an author (Greek) and I didn’t know the exact genre I wrote one of my books. We are using english deffinitions, so somone said my book is dystopian, some cyber punk but now I can say “I wrote a pure speculative”. I wrote (2008) what Athens will look like at 2018 from politikal,social,enviormental point of view. (I apologize for my very bad english).

Hi Nikos! I’m so glad it was helpful for you. Dystopian and cyberpunk are just more specific sub-genres of speculative fiction. So yes, it sounds like you can describe your book as “speculative.” Good luck with it!

Pingback: Genres Wk.1 – Speculative Fiction and Solarpunk – Archivist Tara Belle

This was incredibly helpful and just what I needed. Thank you!

I’m happy to hear it!

Pingback: Australian female fantasy writers, what makes them so magical? – Tayla Bosley

Pingback: Spring Reads 2018 Book Review: The Book of Air by Joes Treasure

Pingback: Genre Angst — Science Fiction vs. Fantasy – BakerDavid.com

Pingback: A review of The Book of Air by Joe Treasure – Compulsive Reader

Pingback: Why I’m Down with “Speculative Fiction” | Bakhtin's Cigarettes

Pingback: What is Speculative Fiction? – Space Age Mermaid

Pingback: Novel Recommendation: Little Mushroom by Yi Shi Si Zhou – Practical Folklorist

Pingback: January Book Club: Nordic Visions – Nordiska's Blog

If it’s fiction it’s speculative. If it’s fiction it didn’t happen. Any story about things that didn’t happen (or haven’t happened) is speculating on what if this did happen. Even if all the things that happen in the story are known to be possible it would have to be an unique nonexistent combination of events and characters for it to be classified as fiction.